![]() |

| Yes, yet another "List Post" |

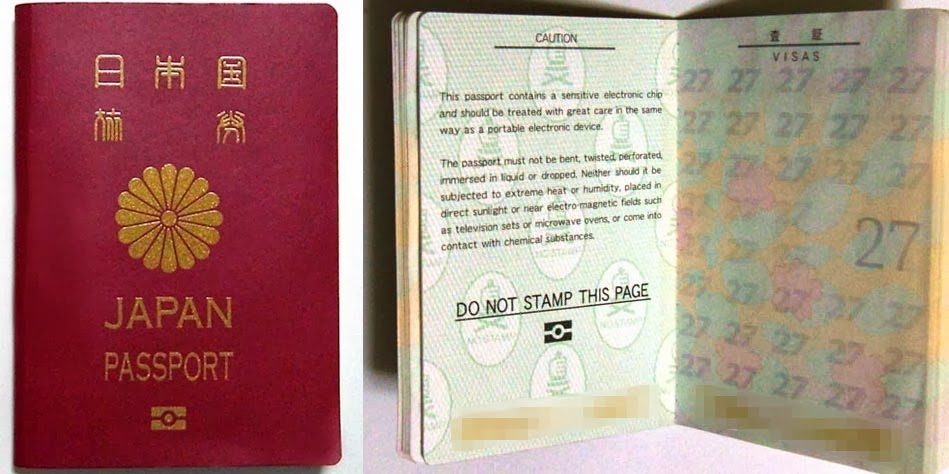

So your dreams have come true and are close to realizing your dream of living in Japan permanently and becoming a national of the country! A country that speaks, reads, and writes Japanese...

Before you came to Japan, you may have had a few years of "college Japanese" under your belt, or you're starting with a blank slate. Either way, here are some things that me or another long-timer I know has either done or wished they had done from day one in Japan. A lot of these things were not immediately obvious when I first started learning Japanese and living in Japan over two decades ago. I hope they can help you.

This post is actually a re-post from a old now defunct blog I wrote called "Nippon: Until Death Do Us Part". It was a relatively popular post. I thought I'd never cover topics such as Japanese language learning on this blog/site, but as this article dealt with learning Japanese for long term life in Japan, and Japanese language is a skill you will probably need to pass the naturalization process as well as to live the remainder of your life in Japan as a citizen, I've decided to re-publish it with a few updates.

Disclaimer: If your goal for learning Japanese is to pick up enough for sightseeing or a six to twelve month university or corporate exchange program, you may not find the below of value. There are plenty of phrasebooks and "learn Japanese in 72 hour" programs which will teach you enough Japanese for greetings and salutations, ordering a beer, buying something, and indicating that you're lost. The steps I list below below are overkill for tourists, exchange students (unless you're studying Japanese!), and international businessmen.

These ten steps are for those wishing to pick up good habits by learning Japanese correctly, for long term life (i.e. naturalization) and work in Japan.

① Avoid ローマ字 from day one

![KODANSHA'S furigana JAPANESE DICTIONARY]() |

| This should be your first textbook |

It's very, very tempting to try to jump start in the beginning and rely on

ローマ字 ("Romanized Japanese," transliterated Japanese) for a few lessons. Because you may not be used to writing Japanese quickly, you'll be tempted to take notes in

ローマ字. Don't.

Here's why: the longer you learn and live in

ローマ字, the longer it will take to reverse bad pronunciation habits that you'll develop because of it. You won't be able to avoid it. If your native language uses Latin letters, your brain won't be able to help itself and will cluster and find patterns and rhythms and sounds associated with your native language, which is burned into your brain. Consider the following paragraph:

Aoccdrnig to rscheearch at an Elingsh uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht frist and lsat ltteer is at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae we do not raed ervey lteter by it slef but the wrod as a wlohe.

If your native language is English, you probably were able to read the above relatively easily. Your brain is programmed to extract your language when you come across your alphabet without thinking. Likewise, it will be extremely difficult to reprogram your brain to break the rhythms, vowel and consonant associations associated with seeing English letters if you're reading Japanese with Latin letters.

To see the above example in reverse, try showing a Japanese person (not a language teacher) a long paragraph of Japanese text written in

ローマ字 and ask them to read it quickly and naturally. Show them the same paragraph written in

仮名 (Japanese syllabet) and ask them to try again.

there are at least 3 ways to transliterate Japanese syllabet| 仮名 | 日本 | 訓令 | ヘボン

(Hepburn) |

|---|

| 平仮名 | 片仮名 |

|---|

| し | シ | si | si | shi |

| じ | ジ | zi | zi | ji |

| ち | チ | ti | ti | chi |

| ぢ | ヂ | di | zi | ji |

| つ | ツ | tu | tu | tsu |

| づ | ヅ | du | zu | zu |

| ふ | フ | hu | hu | fu |

| しゃ | シャ | sya | sya | sha |

| じゃ | ジャ | zya | zya | ja |

| ちゃ | チャ | tya | tya | cha |

| ぢゃ | ヂャ | dya | zya | ja |

| しゅ | シュ | syu | syu | shu |

| じゅ | ジュ | zyu | zyu | ju |

| ちゅ | チュ | tyu | tyu | chu |

| ぢゅ | ヂュ | dyu | zyu | ju |

| しょ | ショ | syo | syo | sho |

| じょ | ジョ | zyo | zyo | jo |

| ちょ | チョ | tyo | tyo | cho |

| ぢょ | ヂョ | dyo | zyo | jo |

You'll find that Japanese, whose brains are programmed from early childhood to read

仮名 and

漢字 (Japanese Han characters), cannot read

ローマ字 naturally.

ローマ字 has little use in real world Japan outside of signs for tourists, decorative effect, in places for international communication, and in devices that are too primitive to support non-English alphabets (software made in the 20th century prior to

Unicode). Because of this, you'll often catch misspellings, inconsistencies such as the transliteration —

ヘボン式 (Hepburn's dictionary transliteration style),

訓令式 (government transliteration style), and

other transliteration systems— being randomly mixed together, missing

長音符 (long vowel notation), and inconsistent 「

ん」 transliteration all over Japan.

Why are there so many careless mistakes in

ローマ字 in Japan made by Japanese? Because the Japanese don't care. It's not the script they read.

When you purchase your first Japanese dictionary for foreigners, purchase one that uses

仮名 (Japanese syllabet) and

振り仮名 (syllabet ruby annotations) exclusively. This will also teach you and improve the speed of your sorting skills, which is important for looking up information in everything from cell phone address books to finding music, books, and videos in collections.

② Focus on pronunciation from day one

![Dozo yo ro shikoo]() |

| Don't let your Japanese sound "romanized" |

Japanese textbooks for English speakers don't pay enough attention to pronunciation. They usually teach English speakers:

- that the vowels are close to Spanish

- that the Japanese "r" is neither an English "r" nor an English "l"

- how to pronounce 「つ」

And that's about it.

Textbooks assume you'll get the rest by listening and mimicking. Considering that a textbook knows it needs to reward its learners with quick practical language success, you can't blame them for being soft on perfect pronunciation. Compared to some Asian languages, an English speaker can be off-and-running and saying things which are mostly understood by native speakers on Day 1, while learners of other languages are struggling to get the alien tones, vowels, and consonants, which are nothing like English, mastered.

But if you learn Japanese without painstakingly practicing the pronunciation, you may end up developing bad habits that will take a long time to correct. There are a lot of subtleties that a properly trained — not a friend or language exchange partner — but rather a teacher who has been formally trained in

TJFL, who can help you with:

- They can use mirrors and video to show when your tongue is in the wrong position, or when your mouth is too round (example: English speakers tend to round their mouths much more for the consonants "w" and "r" compared to Japanese. They also bite their bottom lip for "f," but the Japanese don't do this for the sound 「ふ」

- They can use recorded tape to show you how English speakers tend to "slide" their vowels at the end of words, whereas Japanese cut the air and delivery so the vowel ends sharply.

- They can teach you how to master air control through your nose and mouth for the consonant "g" as well as for the sound 「ん」

Even with a professional teacher's help, you'll probably never sound native. But you

can sound fluent, such that a Japanese stranger who is not used to hearing foreign-accented Japanese can understand your every word even if they're not used to your accent.

So ignore the books and the people that tell you that Japanese pronunciation is easy. It

is easy from the aspect that there few consonants (10) and vowels (5) compared to other languages — and you can mangle the pronunciation pretty badly without completely losing comprehensibility. But why settle for comprehensible, when with a little extra effort at the beginning of your learning, you can sound good?

Here's three final reasons to learn how to pronounce things properly:

- It's hard to sound cool or professional if you have bad pronunciation. There's nothing worse than trying to impress somebody and they can't help suppressing a smile because they've never heard an expression in heavily accented language before. If you're trying to impress, it's not just vocabulary. It's the delivery of that vocabulary.

- It's hard to sound romantic if you have bad pronunciation. Imagine you've spent a week building up the courage to tell that special someone how you feel. Will they say "yes, me too!"? Will they say "no?" Or will they say "can you repeat that a little more slowly please?"

- It's hard to express anger or displeasure if you have bad pronunciation. Swear words and threats don't sound scary if the object of your anger has to concentrate to understand you. You can ignore this advice if you're huge and physically intimidating. Most everybody else though wants to deliver their dissatisfaction in such a way that it doesn't cause snickering.

③ Annotate ALL words in your notes with pitch

![]() |

| This should be your second textbook. |

This is also part of pronunciation, and the difference between somebody that sounds fluent/borderline native and somebody that sounds like a foreign learner. Japanese dialects do have a high and a low pitch for the syllables. They are not as critical to comprehension as

tones are for languages like Chinese. Most Japanese can understand most of what a non-Japanese person says, through context, even if the pitch is completely messed up. If there's no context, though, they'll have to guess.

For example, if you say the single word

はし and you don't use it in a sentence, you need to use the right pitch so people know which

はし you're talking about: bridge (

橋), chopsticks (

箸), or edge (

端).

Unfortunately, finding a Japanese learner's dictionary that annotates the high-low pitches on all the words is difficult. Japanese often use the

新明解日本語アクセント辞典 (New Clear Japanese Accent Dictionary). Even if you own an accent dictionary, make sure, in your notes, that you annotate every single word you write with the pitch. And make sure your teacher corrects you when you use incorrect pitch; less strict teachers — used to teaching casual students — will let pitch slide so long as it's comprehensible.

Also, the pitch patterns are different for different dialects — in particular,

関西弁 (Western Japanese dialect). Learn the pitch for

共通語 (common dialect/language).

④ Don't just study with gimmicks or software/video

![Remembering the Kanji]() |

| The James W. Heisig series: overrated |

Repetition with both written and listening & repeating components works best. Don't just mentally read & answer the exercises in the textbook. Copy the questions longhand whole to a notebook along with the answers.

Verbally say and hear everything you write.

There are tons of books with mnemonic systems. Maybe they work. Maybe they don't. But repetition

does work. Nobody likes to hear that. Just like nobody likes to hear that the foolproof way to lose weight is to eat less and exercise more. Because it's hard work. Much like gimmick diets, you will meet people from all walks of life who swear by some learning gimmick.

You may have noticed that the people who succeed at losing weight using a gimmick diet succeed because they're somehow burning more calories than they're taking in, but they believe it's the gimmick part of the diet that's making them lose weight. People that succeed with the gimmick Japanese study systems are similar. When you look closely at what they're doing, it boils down to more Japanese and less English.

You should approach learning a foreign language the same way you would exercise and diet. The exercise is the endless repetition of writing of the same words and phrases — longhand — over and over. It's the endless oral repetition of your written notes. It's the endless repetition of reading the same phrases over and over. The diet part? That's refraining from using too much of your native language in Japan.

Finally, and this is a hard piece of advice because I live and work on the Internet and with computers: don't use software

exclusively to study and learn. True, with modern operating systems you can display and input Japanese without having a firm grasp of the language. There are now countless instant translation systems. These are great tools for day to day work. But they won't help you once you get yourself into a situation where you're unplugged and off the grid.

Do use electronic devices for casual look up of words while on the street or working at the computer. Just don't use them as a substitute for good old fashioned hand writing, oral repetition, and exercises in homework and classroom work.

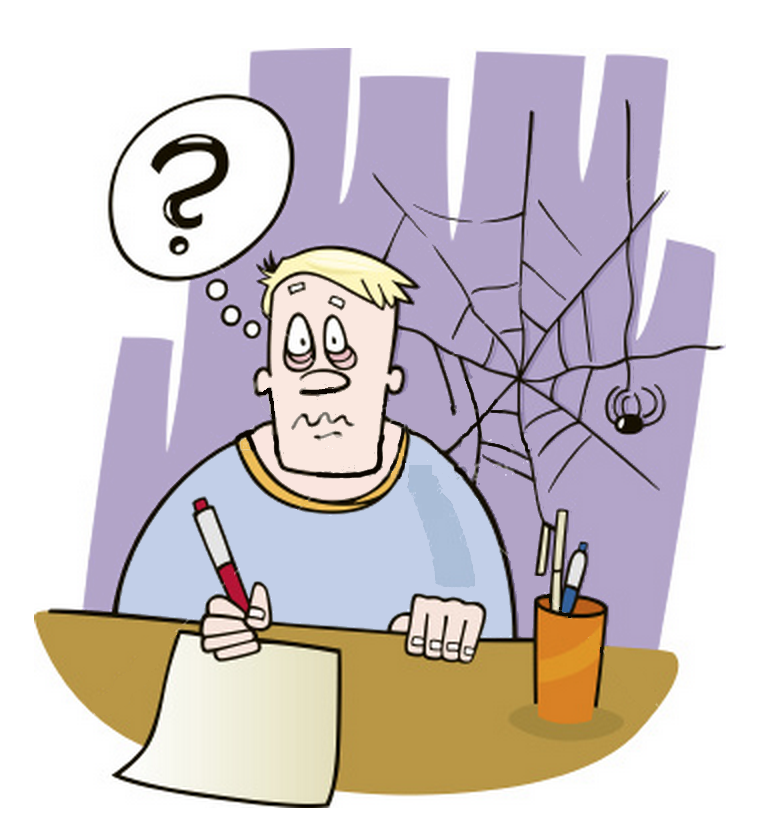

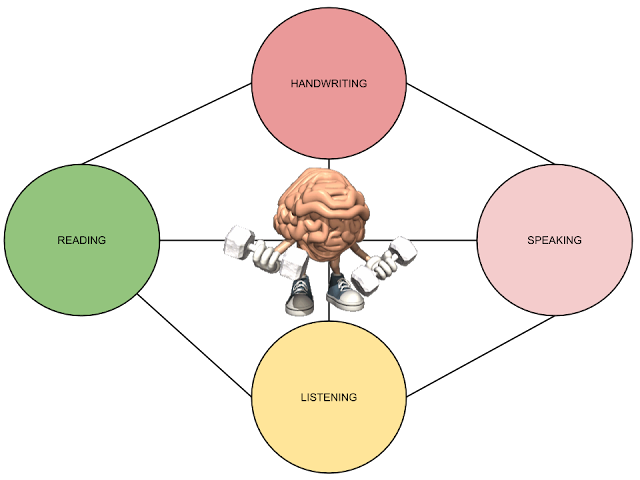

![]() |

| Proper foreign language learning uses all four language skills simultaneously to connect the abilities for the same word or concept together in the brain for better retention, recall and mastery |

It's great that there are so many

SRS flashcard and drills and vocabulary and quiz & test apps available for mobile devices these days. They make studying in one's spare time while riding on a train very easy.

However, too many people use these systems exclusively without doing enough studying that utilizes all four (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) abilities at once. This usually means their reading ends up being their strongest ability, and speaking & writing ends up being their weakest ability. This seems counterintuitive, as many people say that the reading and writing is the most difficult aspect of Japanese due to the thousands of characters.

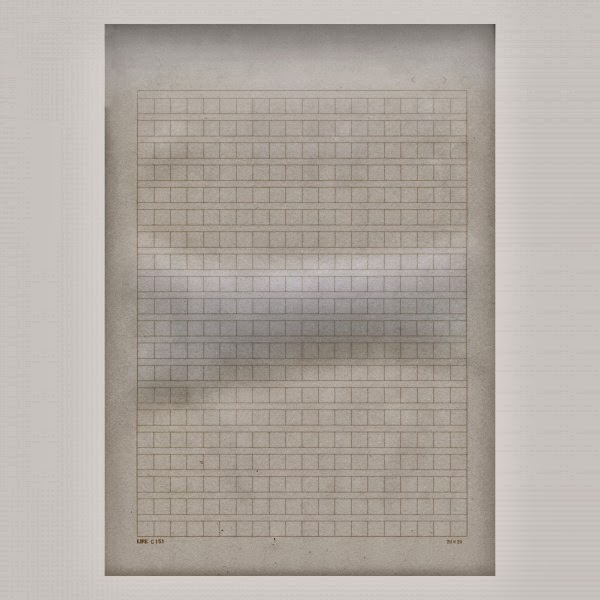

⑤ Use the same tools that Japanese children use

In addition to the

英和・和英辞書 (English-Japanese · Japanese-English dictionary) and the

漢英字典 (Japanese charactery→English dictionary) which are useful for studying

JFL, you should also purchase a

国語辞書 (Japanese-Japanese dictionary) and a

漢字字典 (kanji character dictionary)

for Japanese grade school students such as a

例解学習 (illustrative learning) edition in order to study Japanese

as your second language. The definitions and explanations in these books are written in a simplified manner. You won't need another dictionary to understand the dictionary, and it will keep your brain in "Japanese mode," which will help you speak and write in and think about Japanese in Japanese rather than go through internal translation and interpretation, which will make your thoughts sound unnatural and awkward. By reading Japanese definitions written for Japanese, it will also help you learn how to explain abstract concepts when you need to explain something to Japanese that you either don't know or can't recall the word for.

![]() |

| Workbooks for elementary school children are surprisingly good for those learning JSL. |

When memorizing

漢字, utilize the huge amount of resources within Japan designed and written for Japanese schoolchildren. Don't dismiss these as simple workbooks for writing the same character over and over. There are those, but the good books will focus on total mastery of vocabulary, such as synonyms, antonyms, close-but-incorrect characters,

四字熟語 (four character compounds),

部首 (character radicals),

書き順 (stroke order), and

画数 (character stroke count). Investing in this will give you the same library, sorting, and collating skills that your Japanese peers will have. Also, you can't use computer handwriting recognition systems unless your stroke order and count is correct or close.

⑥ Ignore those that discourage Japanese use

![]() |

| ジャパニーズ マザーファッカー! ドゥ ユー スピーク イット? |

While there are a few jobs in the Japanese marketplace where you may be the only non-native speaker of Japanese, chances are you'll have at least one or two coworkers who are also non-native Japanese speakers. They will want to speak English, and they will want

you to speak English.

Don't.In the workplace, remember that Japanese is an asset and a job skill that differentiates you from other non-Japanese skilled workers. Don't worry about speaking English for the sake of the other non-Japanese.

The vast majority of the non-Japanese you work with in Japan will be gone within five years. If you plan to be in Japan long term, it's your Japanese coworkers that you want to establish good communication channels with. Don't ever put yourself in a position where a Japanese worker is hesitant to talk to you because they are not sure if you'd understand their Japanese or they would understand your English.

There is a little bit of etiquette that one should know and practice:

![]() |

Japanese amongst Americans

is only not unusual in Hawai'i |

Don't speak Japanese to Japanese when you're not in Japan if there's one or more persons that can't speak the language in the group. Especially strangers. Unless you're in Hawaii, which is practically the 48th prefecture of Japan. "When in Rome…"- Don't use Japanese in such a way that it makes your non-Japanese coworkers, who are learning the language and are perhaps not as good as you, look bad. So if you're in a mixed work group of Japanese and non-Japanese and there are some language beginners or intermediates in your group, keep the language at a level so they can understand and participate when they're part of the conversation.

![America's Meltdown: the Lowest-Common-Denominator Society]() |

Avoid the LCD trap by associating

with people whose Japanese ≥ yours |

You may notice that Japanese will do this as well. If they are in a group of non-Japanese, they will modulate their language use (using simple Japanese or switching to English) to the person in the group with the lowest ability level.

This is another reason why, for professional reasons, you should avoid being professionally associated with those who can't speak Japanese during work hours if part of your professional ability consists of your ability to communicate effectively to Japanese speakers. ![The Golden Rule]() |

“do unto others as you would have them do unto you”

『己の欲せざるところを人に施すなかれ』 |

Never rate, judge or comment on another non-Japanese's Japanese level. Either to non-Japanese or Japanese. The only exceptions to this are when evaluating job candidates or if another person judges you. See: The Golden Rule.- Likewise, never rate or judge another Japanese co-worker's English ability. See: The Golden Rule.

- Never expose a poser overseas. At social parties overseas your hosts will inevitably learn that you live in Japan and will introduce you to so-and-so which "lived in Japan" (one year or less on an school or work exchange program) and possibly studied Japanese in college for a few years and "is completely fluent / native." Most of the time, they can't speak it to save their lives. Padding one's résumé with a foreign language you can't really speak or understand is a timeless tradition. If that language is obscure in the United States (in other words, anything except for Spanish), all the better as the chance of being tested is minimal.

![H.R. Your accomplishments speak for themselves. Unfortunately for you I'm completely fluent in exaggeration.]() |

| [ I see a lot of LinkedIn resumes that list "business level" Japanese ] |

Your hosts will expect you to engage in some banter. The Résumé Padder is hoping that you are as much of a poser as they are. Let them off the hook easily. Say two or three short sentences that are ideally found in page one of a beginner's textbook ("My name is _____.", "Where do you live?", "Nice to meet you.") and abruptly end the conversation with something that will get a laugh from the people around you ("Wow! I didn't think I'd have an opportunity to speak Japanese here!"). The people around the two of you can't understand the Japanese anyway, so they can't tell the difference between a beginner and a lifer. Monolingual Americans can't handle more than 15 seconds of foreign language without feeling uncomfortable so it's unlikely they'll urge you to continue.

If you "out" a language poser overseas, all you'll do is make other monolinguals in the group empathize with the exposed, and they'll think you're a jerk for humiliating the poser.

If the poser attempts to leverage their phony skill into a Japanese related job, karma will catch up to them and they will be exposed.

If you're serious about your career in Japan at a Japanese company, then keep the foreign language to a minimum. There are three exceptions:

- If your boss or superiors or customers that you're talking to can't speak Japanese

- If your work environment has a 100% English in the workplace rule. But be careful and realize that many work environments have two environments: foreign language environment(s) and the "real" environment. The "real" environment is usually where the career people are that get promoted and where the management track is.

- If the cost of making a mistake or losing a sale due to language miscommunication or nuance is greater than the benefit of Japanese. You can switch to your native language for critical problems and switch back to Japanese for non-critical situations when you're still learning the language.

![Gaijin Bar]() |

Hanging out with foreigners too much

isn't good for your psychological health |

The time for bonding in your native language and bonding with your non-Japanese associates is

after work.

This is an extremely difficult habit to form. The temptation to use the speed and accuracy of your native language, even for the little things, will be great. The stress of working in a foreign language will also be tough. It will be very tempting to use your native language to make your life easier.

One final reason to use Japanese as often as you can in the workplace: If people get used to hearing you speak English, they will get used to the cadence and tone and your English personality. Many people's personalities seem different when they speak in a foreign language. If people get used to you in English, it can be hard for them to get used to the "new you" when you switch languages. Your personality imprints on people in the first language they meet you in, so it can be jarring if you switch.

Also, if you switch into Japanese in the middle of conversation and your coworkers are not used to it because you haven't made it a habit, your coworkers may think you're switching because you think little of their English ability and could take offense.

⑦ Ignore the "international" Japanese

![United Nations flag]() |

If you want to be truly international in Japan

use Esperanto, not English |

Japanese aren't usually taught that internationalization includes non-Japanese living in Japan and speaking Japanese. To them, internationalization is Japanese going to foreign countries and speaking foreign languages.

If you've been in Japan in a non-tourist setting, you've probably already met this person. They speak the best English in the company (or at least they tell everybody they do). They are always part of the welcoming committee. They are the unofficial interpreter and translator for all matters foreign.

They don't want you to speak Japanese. They don't want you to understand Japan

too well. They've spent many years of their life marketing themselves as the official foreigner liaison (be it customers or internal staff). By speaking Japanese, you reduce their job responsibilities. It also reduces the amount of control they have over

you in the workplace. If you use the international person, your world is completely filtered through them. Even if you don't report to this person, they indirectly control you because they control your access to your company's (Japanese) information, connections, and politics.

These people mean well. And they are useful. Just not to you.

⑧ Ignore people that tell you to use "real" Japanese

![Making Out in Japanese]() |

you won't need this if you

really learn the language |

Thanks to the success in the exportation of Japanese pop culture (

"Cool Japan": J-Pop,

アニメ (animé / Japanese animation/cartoons),

漫画 (Japanese comics), and the Internet) and a generation of

英会話 (English conversation) school employees that learned Japanese from their boyfriends and girlfriends at bars and nightclubs, there's a fad that encourages the speaking and writing using "the stuff they don't teach you in textbooks." They assume that because they can speak street or slang or casual Japanese, their Japanese is more "authentic" and thus better than those that use the

です・ます (formal/polite) style that's usually taught initially by textbooks. This "real Japanese" may substitute for small talk and pick up lines and appear to be clever banter at clubs,

飲み会 (events involving alcohol) and web bulletin boards, but it won't get you very far in the employed world. It's easy to copy/paste a phrase you found on a Japanese web

BBS/forum, omit your

助詞 (Japanese grammar helper particles), and spout crowd-pleasing catchphrases from popular shows.

Is there a time and place for casual Japanese? Of course there is. The problem is that most people go overboard.

Once your fundamentals are sound, learning the informal language is easy. It's

much harder to speak in a business setting, acting and speaking in age appropriate — which I'm assuming is post-degree and over twenty (20) years old — language, and talk about complex topics.

Ignore the people that say you'll never have a need to learn

敬語 (formal / polite / respect grammar / language) — even Japanese will tell you this — unless you want to limit your career options to jobs that will never require you to use it; those jobs are usually not very high paying and have limited room for career advancement.

![Colloquial Kansai Japanese]() |

Not needed to be taken seriously,

even in Osaka |

Don't worry about speaking in the local dialect, be it

関西弁 (Western Japanese dialect) or something else. Unless you're a linguistic genius or a child, it's unlikely you'll ever speak Japanese without having an accent. And there's nothing wrong with that. You can speak fluently and still have an accent. The key to most Japanese dialects is not so much the vocabulary or modified grammar, but rather the subtleties of the accent. Speak in

共通語 (common dialect/language). Learning to understand the dialects is important, but not difficult. You'll see other non-Japanese speaking a little dialect here and there and getting some yuks and applause from the Japanese after hours while drinking. But this is more because seeing non-Japanese (especially non-Asian ones) speaking Japanese is still a novelty. Seeing a non-Japanese speaking dialect is even

more of a novelty.

If you want to be taken seriously, speak in slang-less standard dialect.

⑨ Don't let negativity or "praise" discourage you

It will only take you a few weeks before you'll figure out that the phrase

「日本語、上手ですね」 ("[Your] Japanese's good, huh?")

actually means "Thank you for trying to learn our language." They're just being polite and showing genuine surprise/gratitude that a non-native speaker would attempt to learn Japanese beyond tourist level.

Here are some other things you will encounter:

- You will encounter people who, the minute they sense you're struggling — or worse, you aren't struggling but your Japanese is accented or you made a slight grammar mistake so they assume you are — will switch the conversation into English.

- You will encounter situations where you're trying to be taken seriously but people either laugh at mistakes or nitpick at the grammar and ignore the content of your communication.

- You will encounter people who laser focus on the fact that you're speaking Japanese rather than the content of your Japanese.

- You will encounter countless Japanese in the service industry who, upon encountering accented Japanese, will either stare at you like a deer in headlights, or they will give an embarrassed smile and run and escalate to their manager.

People will tell you over and over that no matter how hard you try, you will never master the language. Worse, they'll change the topic and segue into how it's pointless to try because you'll "never be accepted" no matter what you do.

Don't let these people discourage you. You need a thick skin.

Let your teacher be your critic. Let the standardized tests be your critic. Let yourself be your critic. Ignore everybody else.

⑩ Be patient

![Progress: Isn't Always]() |

| Sometimes you'l feel that your Japanese can't improve or is getting worse |

To go from knowing nothing in Japanese to fluency in Japanese, no matter your native language, takes the average person

five (5) years. Some linguistically gifted people are going to do it in four years. Some slower people take six years. There are two conditions to the five year rule:

- You must be exposed to Japanese from morning to night, and make an effort to use the language from morning to night. The reason you meet people in Japan who have lived in Japan for over a decade and can't speak the language is because they live in an English bubble:

![]() |

100% Japanese: work, play, home

5 years: nothing to fluency |

- They work for an company where they mostly speak English and deal with their coworkers in English all day long with only smatterings of Japanese.

- They go home to a spouse and children that speak English.

- They consume mostly English newspapers (including news about Japan in English) and English television (by listening to the second language option for movies and news). This information source is extremely abridged compared to Japanese sources.

- They hang out in bars, venues, and restaurants that are popular with non-Japanese and the Japanese that like to hang out with non-Japanese (and speak English).

- The primarily use the social features of the internet (social networks, video chat) in English.

Thus, it is difficult to achieve the five year benchmark if your job requires you to speak English (example: English teaching or working for a foreign multinational) most of the day. ![]() |

language exchange is inefficient

and the quality of learning spotty |

You must formally study the language — ideally with a professional accredited native Japanese teacher — and subject yourself to formalized evaluation using standardized tests such as the 日本語能力試験 (JLPT) and 日本漢字能力検定 aka 漢検 aka JKAT— for about 200 hours (not counting homework) a year. - If you can afford it, you should use a private teacher rather than study in a group once your language level is past beginner.

- You should use a certified teacher who has passed the 日本語教育能力検定試験 (JLTCT). Unfortunately, these teachers are expensive and hard to find.

- Do not dictate the curriculum or the type or amount of homework or the teaching style. As teachers need the work and money, they are often under pressure to be seen as "flexible" rather than making sure how they are teaching is the most effective way. If your teacher is really a pro, he or she will know what's best for you.

- If you can't find or afford a pro with certification, try to get a teacher that is the same sex as you. This is harder than it sounds because more women go into foreign language teaching than men. The reason having a same sex teacher helps is because the language style is different for men and women. If you're dealing with a pro with certification, this is less of a problem as a pro will be more observant of sex and age related differences in language. If you have a choice between getting a teacher that is the same sex (and/or age range as you) and a certified teacher, though, always pick the certified teacher.

Despite doing this, you will discover that learning Japanese is not like exercising and dieting in that your graphed progress will not be linear or wavy. Rather, you will feel that you have been studying for months and day-to-day communication does not seem to improve and you'll be frustrated.

Suddenly, and inexplicably, you'll notice one day that a lot of communication challenges will be a lot easier. Encouraged by this, you'll study even more and more. However, you won't notice any improvement again for many months. Your ability will seem to flat line, despite your efforts and studying. Just when you're about to give up and you think your Japanese will never get any better, you'll suddenly notice that your ability again has mysteriously gotten much better, even though you haven't changed your studying habits or your communication situations.

![]() |

| JLPT N1 (N1級) is presumed to be "100% ability / proficiency" |

Visualizing this on a graph, your language ability, if graphed on paper with the x-axis being time and y-axis indicating perceived ability, will probably look like a stretched staircase rather than a line or a curve.

The important thing is not to give up during those flat line periods and to keep studying.

So that's it. It's a long haul, but very rewarding. And Japanese fluency is the number one way to open doors for non-Japanese that wish to live long term in Japan.

頑張って!

(Good luck! / Work hard! / Go for it!)

.jpg)

_Reception_Center_0688&9-07_cropped.jpg)